The Boy and the Heron: There's a New Hamlet in Town

The Boy and the Heron is the latest animated film by Japanese auteur Hayao Miyazaki. Heron is, as of writing, the number one film in America, which is kind of wild.

It could mean that the only people shelling out for movie tickets right now are Studio Ghibli fans. After all, the economy is pretty bad. You may have noticed.

Alternately, it could mean that Studio Ghibli’s reputation (and that of Hayao Miyazaki) has overcome the American aversion to foreign cinema, be it ever so artfully dubbed.

I can afford to generalize here because it’s true. We Americans like our entertainment— especially the animated variety— to have a nice clear three-act structure. The characters should be lovable, huggable even, and catchphrases should abound.

The Boy and the Heron throws this criteria out the window. The protagonist, Mahito (voiced by Luca Padovan) is a sullen boy deep in mourning for his mother. Mahito is locked up, frowning, quiet. When the movie opens, his father has married his late wife’s sister. Mahito’s father shuttles him off to a new home in the countryside. Wartime deprivation has hit this world: only a frail array of cute little babushkas remain to tend to the manor house. The grandmothers hover over their mistress, who is in a delicate state, to put it delicately.

Something is rotten in the air, though. A malevolent heron lurks about on the estate. Mahito is the only one who sees its superfluous flesh and teeth; the only one who hears its croaked invitation, “your presence is requested.”

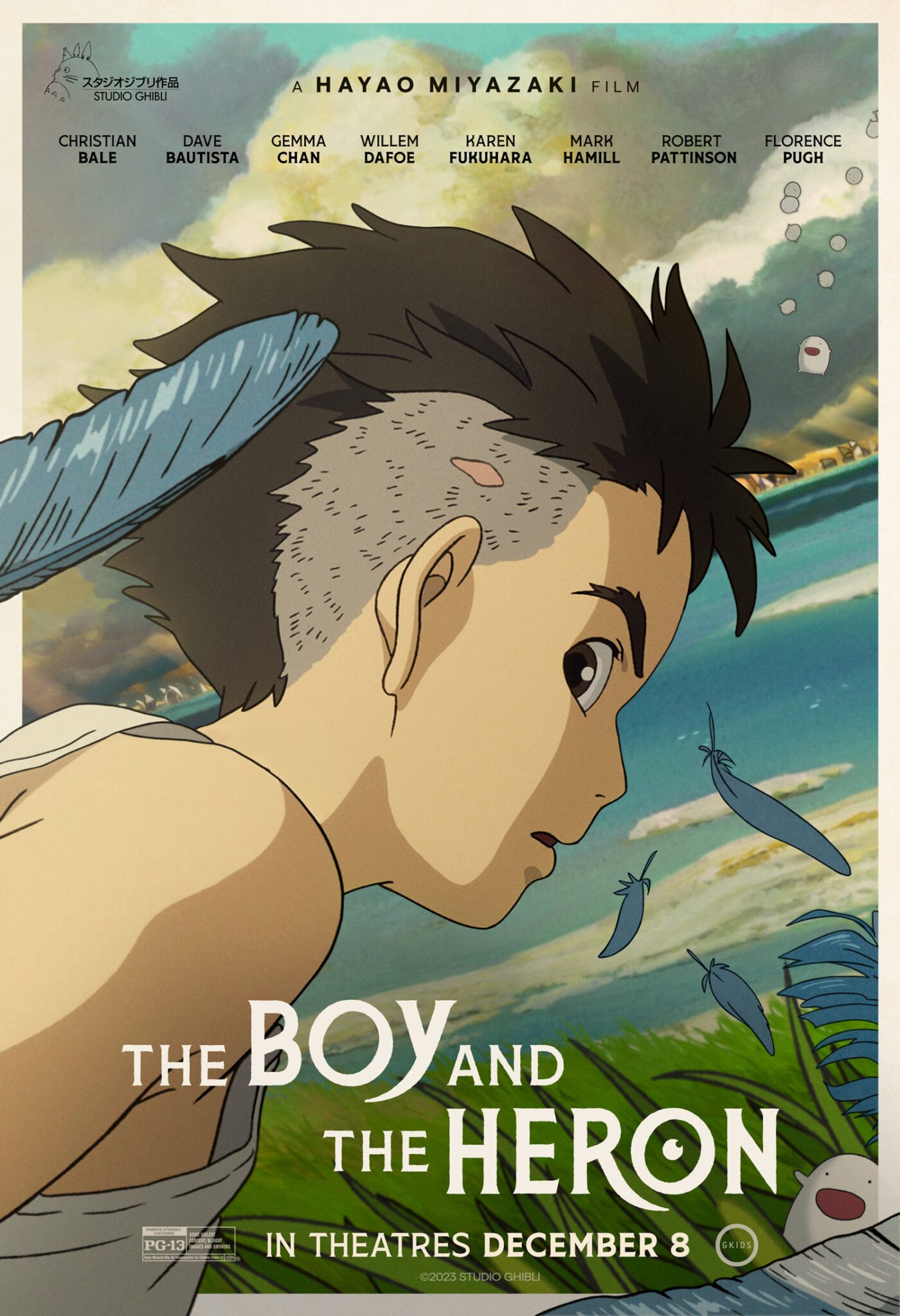

Image ID: Poster for The Boy and the Heron, a close-up on Mahito’s face in profile.

I was lucky enough to see Heron recently at the Alamo Drafthouse in Downtown LA, a business that seeks to keep alive the art of the cinema. It’s where I saw del Toro’s Pinocchio last year. And what did I think of Heron?

Well, it’s brilliant. It’s beautiful. And very strange.

Even in its quieter scenes there is something restless and turbulent below the surface.

People might have said similar things in Jacobean England, you know, when they stepped out of William Shakespeare’s “The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.” They might have blinked at one another.

One would say, “Verily, that was passing strange.”

“Forsooth,” the other one would say, “I thought Hamlet had a happy ending.”

I bring up this comparison because the Internet (at least the corners that I inhabit) usually links Studio Ghibli with certain… buzzwords. Words such as “cottagecore,” “sweet dreams fuel,” “cozy.” Personally, I can’t shake off the idea that Hayao Miyazaki saw one too many Youtube edits and tiktok videos and other bits of fandom fluff that called his artistic oeuvre “cozy.” Something inside the master snapped. He took a drag on his cigarette and said, “Enough of that. Let’s make some nightmares.”

Mahito steps lightly in the manor house. He knows there is a tenuous balance there. The house is pulled in two directions— at one end, the airplane factory run by Mahito’s father. At the other end, the tower behind the forest. Abundant with life, that forest. The Heron is right at home there. At the pier’s edge, the Heron can effortlessly conjure a plague of frogs to swarm over Mahito. During which scene you can almost hear Werner Herzog musing, “I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and… growing and… just rotting away.”

In contrast, the human world is diminishing. What is not consumed by fire is turning shabby, aged, feeble. The human world collapses into ash. Mahito’s father accelerates this process, of course. One airplane at a time.

Let’s review real quick.

A nation at war. Our story dwells on the edge between so-called civilization and the wild world. Mahito is mourning his dead mother. His father has remarried, to his late wife’s sister. And there’s a supernatural creature, shaped like something noble. This creature is determined to lure Mahito off the beaten track, perhaps onto the path of magic.

Mahito, though, couldn’t care less about magic. All that gets him out of his depression is the goal to kill that heron.

Now, when I put it like that— up until the very end— it really does start to sound like Hamlet.

And after all, why not? In a way, Ponyo was a take on The Little Mermaid. Spirited Away has a passing resemblance to Alice in Wonderland.

The Boy and the Heron is an adaptation of a Japanese book, How Do You Live? by Genzaburo Yoshino. I haven’t read Yoshino, I have no idea how closely the film adheres to the book.

On the flip side, I am pretty certain that Diana Wynn Jones’ novel Howl’s Moving Castle doesn’t feature Christian Bale, mid-transformation to a raven-prince-monster, swearing to protect Emily Mortimer as bombs fall around them. I’m pretty sure if that were in the book, I would have remembered.

But I have some thoughts about The Boy and the Heron. And just like I think Shakespeare’s Hamlet could have used an editor, I have some notes for Miyazaki.

I think the Heron could have been more nightmarish.

When we first glimpse the Heron, he is an ordinary bird, and thus, a noble creature without the burdens of humanity. But in short order we see a new facet: the Heron is a ghoul, with bulbous flesh and blunt teeth. A creator of awful puppets, snarling at the threshold of adventure. He blurs the boundaries, he frightens the children, he goes bump in the night. The Heron is terrifying.

And then Mahito shoots him.

“Squawk!” goes the Heron. Wait, he’s not a heron at all! He’s just a short man with an unusually large schnozz, wearing a magical heron suit. He’s cowardly and rather selfish. He is now a recognizable archetype, a Grumpy Old Man Sidekick. He could have been voiced by Danny DeVito and the result may have been more consistent, as opposed to making a character spooky at first, and then goofy. As it is, the viewer gets a touch of whiplash.

In short: Miyazaki could have kept the Heron creepy and I think the movie would have worked better.

I’m not going to do a play-by-play of the rest of the movie, but rest assured, Mahito does go to the enchanted tower, to seek his missing stepmother. A servant reluctantly tags along, an old woman named Kiriko. She’s recognizable by her yellow kimono printed with wheels. Samsara, the wheels of death and rebirth.

Through the tower doors, Mahito finds what can only be called “an undiscover’d country,” an archipelago under a cloudless sky. It is a landscape littered with omens of death— stone monoliths, ravenous pelicans, golden gates.

The rest of the movie doesn’t make a terrible amount of sense, and I am cutting Miyazaki a LOT of slack. I don’t expect his movies to check boxes, or to hit the milestones of a Hollywood script machine. Hell, Howl’s Moving Castle is a movie I adore and I still can’t tell if it takes place over a few months or a particularly lively weekend.

For its apparent spaciousness, the Undiscover’d Country is a land of scarcity. One powerful scene shows Mahito gutting a fish bigger than he is. Multi-eyed and brown as mud, that fish. The body swells with vitality and Mahito slices it to feed the Warawara, vague little blobs of cuteness that are, he is told, the promise of future life. The pressure of the knife cutting through piscine flesh— this is catharsis, this is ART. And what does it mean? Who even knows? What does it have to do with the plot? WHO KNOWS?

Perhaps gutting the fish is a form of stress relief.

The Boy and the Heron has a certain stoic quality to it that begins to feel pretentious. One almost wants to call it “masculine.” There is compassion for the peripheral characters, but it lacks the depth of earlier works by the same studio. Still, Mahito picks up enough compassion that he sheds his black-and-white mentality.

As he wanders from one tableau to another, he is looking for Natsuko, his stepmother-aunt— who is, as mentioned before, in a delicate condition.

Miyazaki has never been one to over-explain things. There is a tact about him, and that’s admirable. But when it comes to Natsuko’s condition, the film is nearly tiptoeing around the subject. A trace more explicitness might have been in order, considering this film boasts Big Themes about life and death, the here-after and the here-before. Here, the holy papers of a gravesite can become a mummy’s wrapping; the souls of the unborn float into the sky on double-helixes; a young girl commands the fire that promises to one day consume her. But god forbid we actually talk about pregnancy.

I get it, I get it, being explicit about bodily functions is an American thing. Whatever.

Anyway, Mahito journeys through the Undiscover’d Country, makes some big choices, and in the end he returns home. In fact, a whole panoply of birds accompanies Mahito, all delighted to be restored back to OUR world, to partake in a living, whole ecosystem. There’s almost a sigh of relief— almost. The Heron, shrugging his suit back on, takes it for granted that Mahito will forget everything he’s been through. Mahito isn’t so sure of that.

The movie ends with a small coda, wherein Mahito says a silent goodbye to his room. What has his supernatural adventure brought to bear on Mahito’s life? Heron doesn’t say. This is not the place for pat morals, or easy rules of magic. In a Miyazaki movie, all you can be sure of is this:

One course of life begins and in time, it comes to an end. The wheels of life continue to turn. We are all carried along.

Miyazaki doesn't offer coziness, he doesn’t offer easy answers, but The Boy and the Heron is a thought-provoking journey through death and life and off to the other side. It’s currently playing in select cinemas, so if you can see it on a big screen, don’t miss it.